About The Book

‘I’m working on a novel intended to express the feel of England in Edward III’s time ... The fourteenth century of my novel will be mainly evoked in terms of smell and visceral feelings, and it will carry an undertone of general disgust rather than hey-nonny nostalgia’ – Anthony Burgess, 1973

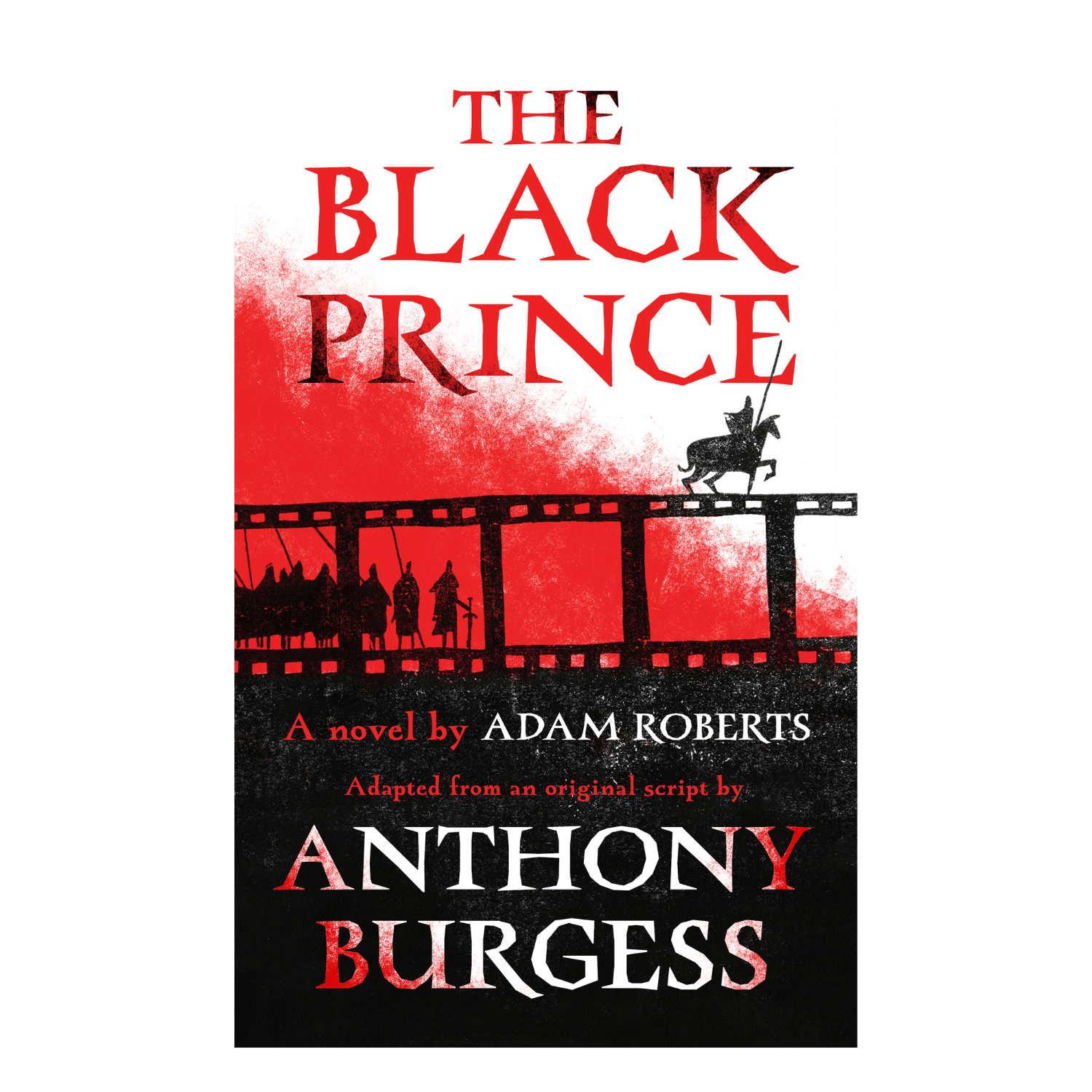

The Black Prince is a brutal historical tale of chivalry, religious belief, obsession, siege and bloody warfare. From disorientating depictions of medieval battles to court intrigues and betrayals, the campaigns of Edward, the Black Prince, are brought to vivid life.

This rambunctious book, based on a completed screenplay by Anthony Burgess, showcases Adam Roberts in complete control of the novel as a way of making us look at history with fresh eyes, all while staying true to the linguistic pyrotechnics and narrative verve of Burgess’s best work.

'The Black Prince is as dark and bloody as its protagonist ... a colourful medieval tapestry combined with the grimness of twentieth-century newsreel' Margaret Drabble, TLS

'A stylistic pastiche that is far more than a tribute act – as though Roberts has dismantled the clockwork that made Burgess tick and reassembled it in a new form' Guardian

‘Burgess’s compulsive inventiveness has found its rightful twenty-first-century heir... cleverer than Cloud Atlas, bloodier than Blood Meridian’ Francis Spufford

Cleverer than Cloud Atlas, bloodier than Blood Meridian

Be a part of our community! 334,112 people from 207 countries have pledged £11,980,334 to fund 646 projects - and counting!