- Home

- This Is Not About You

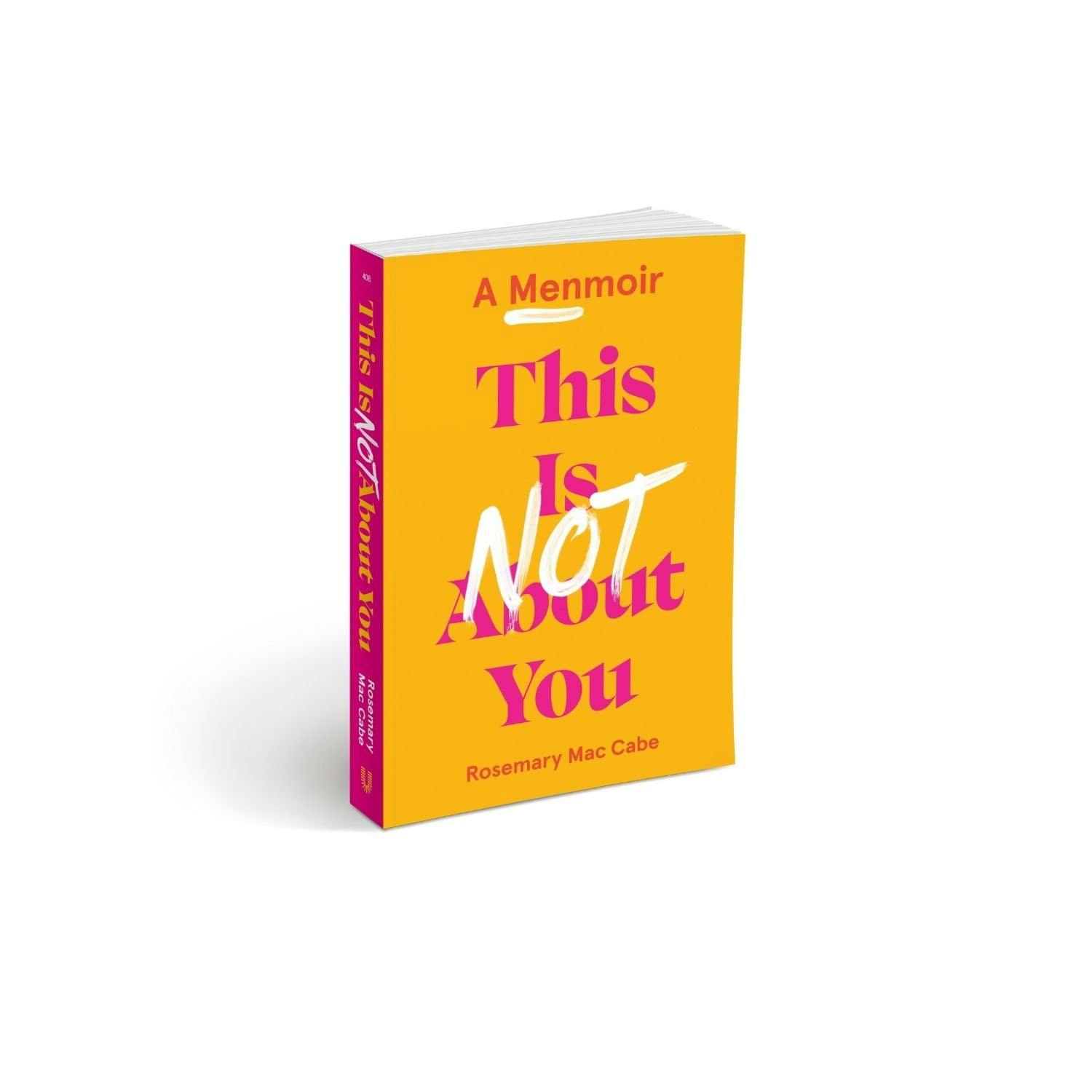

This Is Not About You

About The Book

For once, these men are the objects; I am the subject. Me, me, me.

Rosemary Mac Cabe was always a serial monogamist – never happier than when she was in a relationship or, at the very least, on the way to being in one. But in her desperate search for ‘the one’ – from first love to first lust, through a series of disappointments and the searing sting of heartbreak – she learned that finding love might mean losing herself along the way.

This Is Not About You is a life story in a series of love stories. About Henry, with the big nose and the lovely mum, with whom sex was like having a verruca frozen off in the doctor’s surgery: ‘uncomfortable, but I had entered into this willingly’. About Dan, with the goatee. About Luke, who gave her a split condom. About Frank, who was married…

But mostly, it’s about Rosemary, figuring out just how much she was willing to sacrifice for her happy ending.

Be a part of our community! 334,112 people from 207 countries have pledged £11,980,334 to fund 646 projects - and counting!